One of the great struggles in maintaining a reference collection is the struggle to keep reference materials current. Riedling (2013) recommends that many reference materials be replaced after only 5 years. As the type of person who never likes to throw things out, I struggled with this idea. But it boils down to a quote from Riedling on page 21: "A good reference source is one that serves to answer questions, and a bad reference source is one that fails to answer questions." If a source is out of date, it likely won't answer all questions or, even worse, may answer them incorrectly.

The quote by Riedling above gets to the heart of the role of the reference librarian. Be it maintaining collections, educating students, or performing reference interviews with students, we need to do our best to make sure questions are answered. But how do we do this in the age of google and budget cuts? More and more, our students are turning to the internet to find their answers, and let's be honest, most of us do it too. I have written previously about the pitfalls of Google searches and argued for the use of the book. What if instead of fighting the changes, we leaned into them?

One of the main advantages of printed resources is that they are already evaluated before being placed on the shelves. By keeping it in our library, a resource has received our seal of approval. Students (and teachers) can no longer be certain that the information they find is appropriate. Google searches will return results from authoritative sources alongside random blog posts from those with little to no expertise. It will return works that share terminology, but not the actual topic of interest. Essentially, rather than being able to trust any source they find, students need to learn how to evaluate sources for reliability.

And of course, there is the question of Wikipedia. The main difference between Wikipedia and traditional encyclopedias, whether they be print or digital, is that traditional encyclopedias are written by people selected specifically for their expertise in the topic of interest. Contributors to Wikipedia, on the other hand, are entirely self-selected, and while information is expected to be cited, that's not always the case. We aren't always able to perceive our own lack of knowledge and understanding on a topic, so it's difficult to be sure those contributing to Wikipedia articles know what they are talking about. And that's not even taking into account those posting deliberately incorrect information (aka trolls).

Another issue with relying on google searches is that we miss a lot of the information available. Part of our role as teacher-librarians has always been to teach students how to seek out and find information, and that skill set needs to be applied to the internet as well. I recently learned that search engines like Google only retrieve a small percentage of what the internet has to offer (estimates range from 0.03% to 16%); the rest of the internet is buried under layers of clicks and searches. This leads to a whole new set of research skills that needs to be learned by students and teachers alike. That has morphed to a degree in that we now much also be able to help students evaluate information as well. This change recent to everyone - teachers, librarians, and students. As the closest to this information, it is up to us to lead the charge in information evaluation.

None of this is to say that we should abandon printed resources. They are great for several groups: kids too young to successfully navigate the internet, those without much access to internet or computers, or simply to answer questions quickly and easily from a trusted source. However, we can't just let students run rampant on the internet without a little guidance.

As teacher librarians, our role is becoming ever more complex. We need to teach both teachers and students how to effectively navigate the internet for research, but also when it would be in their best interest to turn to in-library resources (printed or digital). We also need to maintain access to a wide range of digital and print resources for our students, and encourage teachers in familiarizing themselves with the library resources. Some may need more support than others to help them level up their skills with library resources.

Works Cited

Berenstein, Paula (2006). The Kid's Alright (And So's The Old Man). Retrieved from http://www.infotoday.com/searcher/mar06/berinstein.shtml

Dunning, David (2017). Why Incompetent People Think They're Amazing. Retrieved from https://ed.ted.com/lessons/why-incompetent-people-think-they-re-amazing-david-dunning

LaGuardia Community College (2018). Some Fast Facts About the Invisible Web. Retrieved from http://guides.laguardia.edu/c.php?g=762553&p=5467879

Meriam Library (2010). Evaluating Information - Applying the CRAAP Test. Retrieved from https://www.csuchico.edu/lins/handouts/eval_websites.pdf

Neilson, Sonya (2019). LIBE 467 Theme 1 Blog Post: An Argument for the Humble Book. Retrieved from https://svneilson.blogspot.com/2019/01/libe-467-theme-1-blog-post-argument-for.html

Neilson, Sonya (2019). LIBE 467: Collaborating With Teachers to Evolve Their Practice. Retrieved from https://svneilson.blogspot.com/2019/03/libe-467-collaborating-with-teachers-to.html

Riedling, Ann Marlow, Shake, Loretta, and Houston, Cynthia (2013). Reference Skills for the School Librarian: Tools and Tips (Third Edition). Linworth.

|

| Reference librarians connect people with questions to sources with answers. Image care of Careers 360. |

The quote by Riedling above gets to the heart of the role of the reference librarian. Be it maintaining collections, educating students, or performing reference interviews with students, we need to do our best to make sure questions are answered. But how do we do this in the age of google and budget cuts? More and more, our students are turning to the internet to find their answers, and let's be honest, most of us do it too. I have written previously about the pitfalls of Google searches and argued for the use of the book. What if instead of fighting the changes, we leaned into them?

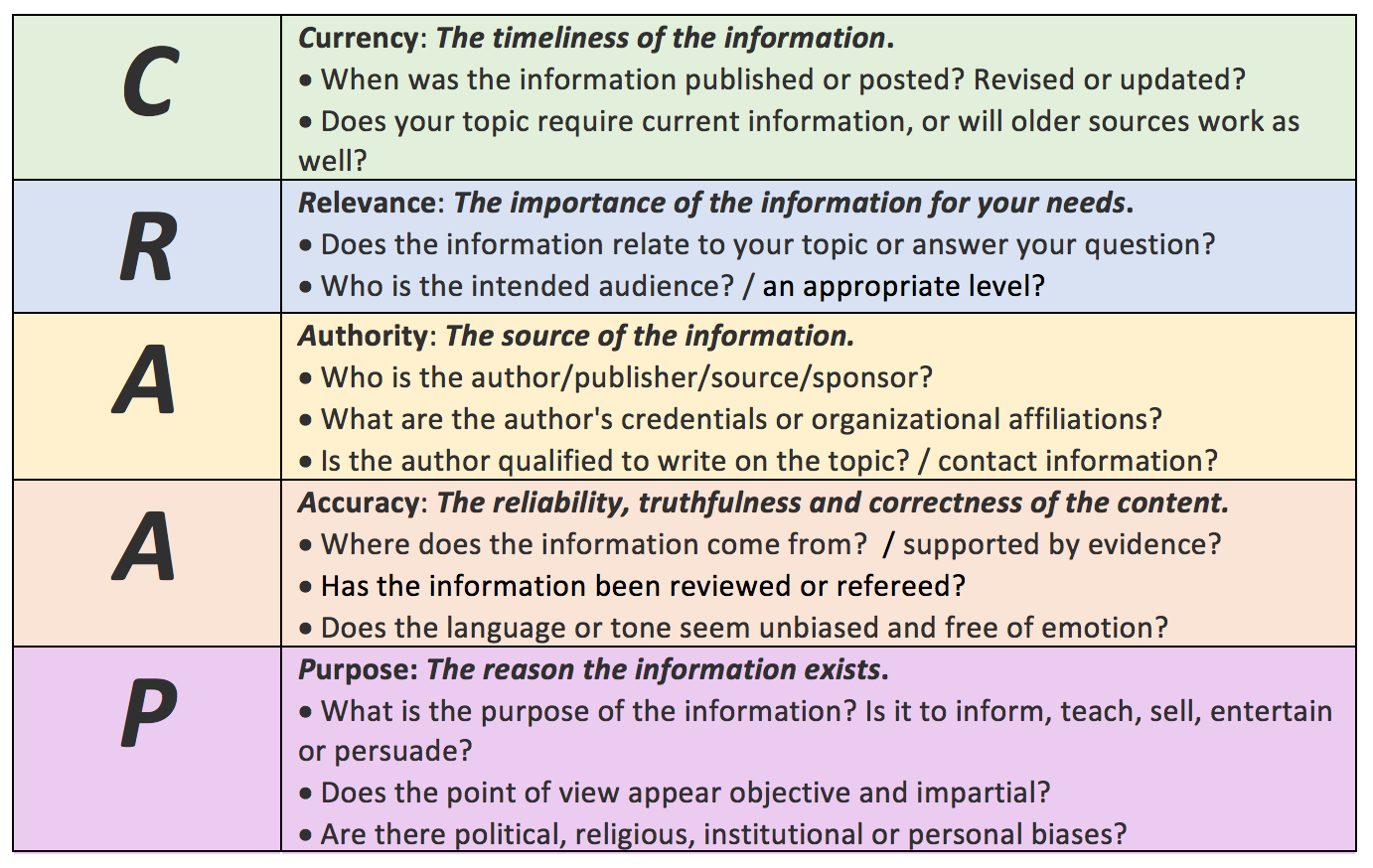

One of the main advantages of printed resources is that they are already evaluated before being placed on the shelves. By keeping it in our library, a resource has received our seal of approval. Students (and teachers) can no longer be certain that the information they find is appropriate. Google searches will return results from authoritative sources alongside random blog posts from those with little to no expertise. It will return works that share terminology, but not the actual topic of interest. Essentially, rather than being able to trust any source they find, students need to learn how to evaluate sources for reliability.

|

| Evaluating sources using the CRAAP test. Image care of Academic English UK. |

And of course, there is the question of Wikipedia. The main difference between Wikipedia and traditional encyclopedias, whether they be print or digital, is that traditional encyclopedias are written by people selected specifically for their expertise in the topic of interest. Contributors to Wikipedia, on the other hand, are entirely self-selected, and while information is expected to be cited, that's not always the case. We aren't always able to perceive our own lack of knowledge and understanding on a topic, so it's difficult to be sure those contributing to Wikipedia articles know what they are talking about. And that's not even taking into account those posting deliberately incorrect information (aka trolls).

| The Dunning-Kruger effect shows how we may be over-confident in our understanding of a given field. Image from Agile Coffee. |

Another issue with relying on google searches is that we miss a lot of the information available. Part of our role as teacher-librarians has always been to teach students how to seek out and find information, and that skill set needs to be applied to the internet as well. I recently learned that search engines like Google only retrieve a small percentage of what the internet has to offer (estimates range from 0.03% to 16%); the rest of the internet is buried under layers of clicks and searches. This leads to a whole new set of research skills that needs to be learned by students and teachers alike. That has morphed to a degree in that we now much also be able to help students evaluate information as well. This change recent to everyone - teachers, librarians, and students. As the closest to this information, it is up to us to lead the charge in information evaluation.

|

| If only it were this simple. Image care of Better Internet for Kids. |

None of this is to say that we should abandon printed resources. They are great for several groups: kids too young to successfully navigate the internet, those without much access to internet or computers, or simply to answer questions quickly and easily from a trusted source. However, we can't just let students run rampant on the internet without a little guidance.

As teacher librarians, our role is becoming ever more complex. We need to teach both teachers and students how to effectively navigate the internet for research, but also when it would be in their best interest to turn to in-library resources (printed or digital). We also need to maintain access to a wide range of digital and print resources for our students, and encourage teachers in familiarizing themselves with the library resources. Some may need more support than others to help them level up their skills with library resources.

Works Cited

Berenstein, Paula (2006). The Kid's Alright (And So's The Old Man). Retrieved from http://www.infotoday.com/searcher/mar06/berinstein.shtml

Dunning, David (2017). Why Incompetent People Think They're Amazing. Retrieved from https://ed.ted.com/lessons/why-incompetent-people-think-they-re-amazing-david-dunning

LaGuardia Community College (2018). Some Fast Facts About the Invisible Web. Retrieved from http://guides.laguardia.edu/c.php?g=762553&p=5467879

Meriam Library (2010). Evaluating Information - Applying the CRAAP Test. Retrieved from https://www.csuchico.edu/lins/handouts/eval_websites.pdf

Neilson, Sonya (2019). LIBE 467 Theme 1 Blog Post: An Argument for the Humble Book. Retrieved from https://svneilson.blogspot.com/2019/01/libe-467-theme-1-blog-post-argument-for.html

Neilson, Sonya (2019). LIBE 467: Collaborating With Teachers to Evolve Their Practice. Retrieved from https://svneilson.blogspot.com/2019/03/libe-467-collaborating-with-teachers-to.html

Riedling, Ann Marlow, Shake, Loretta, and Houston, Cynthia (2013). Reference Skills for the School Librarian: Tools and Tips (Third Edition). Linworth.

A good high level reflection on the key aspects of Teacher-Librarianship as they support information literacy skills and provide important access and guidance. Your writing, evidence and summary are all well done and provide a useful perspective on pretty much the whole course. A little more specific discussion of the modules and topics that pertain only to theme 3 would be beneficial, but you did discuss some of them in general terms. Overall, a useful, authentic look back at your key learning over the last few weeks.

ReplyDeleteHello Sonya,

ReplyDeleteI would like to comment on fake news and facts. Yes, I agree that we are in an interesting area in Teacher-Librarianship with teaching students how to access reliable resources. Information skills is a strong area of interest for me. As an adult, I find that I am still "training" myself to carefully evaluate information on the internet, and this requires that I am cognizant of doing so. I think teaching students information skills requires that it be taught consistently so students become active and habitual in using these critical thinking skills.

Thank you for your great post!

Raquel